This Time Was Already Accounted for on 527 I Placed It Here Again for Illustration Purposes

| Justinian I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

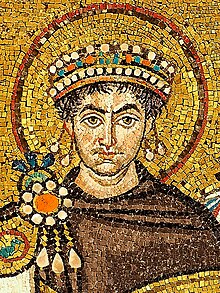

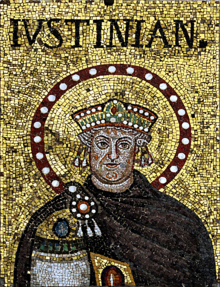

Item of a contemporary portrait mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna | |||||

| Byzantine emperor | |||||

| Augustus | 1 April 527 – 14 November 565 (alone from ane Baronial 527) | ||||

| Acclamatio | 1 April 527 | ||||

| Predecessor | Justin I | ||||

| Successor | Justin II | ||||

| Born | Petrus Sabbatius 482 Tauresium, Dardania (now N Republic of macedonia[1]) | ||||

| Died | 14 Nov 565 (aged 83) Neat Palace of Constantinople, Constantinople | ||||

| Burial | Church building of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople | ||||

| Spouse | Theodora | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Justinian dynasty | ||||

| Male parent |

| ||||

| Female parent | Vigilantia | ||||

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity | ||||

Justinian I (; Latin: Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus; Greek: Ἰουστινιανός Ioustinianos ; 482 – fourteen November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but just partly realized renovatio imperii, or "restoration of the Empire".[ii] This ambition was expressed by the fractional recovery of the territories of the defunct Western Roman Empire.[3] His general, Belisarius, swiftly conquered the Vandal Kingdom in Northward Africa. Subsequently, Belisarius, Narses, and other generals conquered the Ostrogothic kingdom, restoring Dalmatia, Sicily, Italian republic, and Rome to the empire after more than than half a century of rule past the Ostrogoths. The praetorian prefect Liberius reclaimed the southward of the Iberian peninsula, establishing the province of Spania. These campaigns re-established Roman control over the western Mediterranean, increasing the Empire'due south annual revenue by over a one thousand thousand solidi.[4] During his reign, Justinian also subdued the Tzani, a people on the east declension of the Blackness Body of water that had never been under Roman rule before.[5] He engaged the Sasanian Empire in the east during Kavad I'due south reign, and later again during Khosrow I's; this second disharmonize was partially initiated due to his ambitions in the west.

A still more resonant attribute of his legacy was the uniform rewriting of Roman law, the Corpus Juris Civilis, which is still the basis of ceremonious police in many modern states.[6] His reign likewise marked a blossoming of Byzantine culture, and his building program yielded works such as the Hagia Sophia. He is chosen "Saint Justinian the Emperor" in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[seven] Because of his restoration activities, Justinian has sometimes been known every bit the "Last Roman" in mid-20th century historiography.[8]

Life [edit]

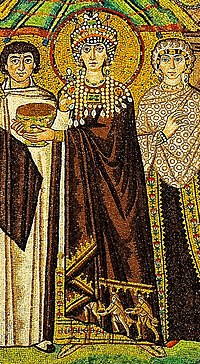

Mosaic of Theodora

Justinian was built-in in Tauresium,[9] Dardania,[ten] effectually 482. A native speaker of Latin (perhaps the final Roman emperor to be ane),[xi] he came from a peasant family believed to take been of Illyro-Roman[12] [13] [14] or of Thraco-Roman[15] [sixteen] [17] origin. The cognomen Iustinianus, which he took later, is indicative of adoption by his uncle Justin.[eighteen] During his reign, he founded Justiniana Prima not far from his birthplace.[19] [20] [21] His female parent was Vigilantia, the sister of Justin. Justin, who was commander of one of the imperial baby-sit units (the Excubitors) before he became emperor,[22] adopted Justinian, brought him to Constantinople, and ensured the boy'south education.[22] As a result, Justinian was well educated in jurisprudence, theology and Roman history.[22] Justinian served as a candidatus, one of forty men selected from the scholae palatinae to serve every bit the emperor's personal bodyguard.[23] The chronicler John Malalas, who lived during the reign of Justinian, describes his appearance equally short, off-white skinned, curly haired, circular faced and handsome. Another contemporary historian, Procopius, compares Justinian's appearance to that of tyrannical Emperor Domitian, although this is probably slander.[24]

When Emperor Anastasius died in 518, Justin was proclaimed the new emperor, with significant aid from Justinian.[22] During Justin'south reign (518–527), Justinian was the emperor's close confidant. Justinian showed a lot of ambition, and it has been thought that he was functioning as virtual regent long before Justin fabricated him acquaintance emperor on 1 April 527,[25] although there is no conclusive show of this.[26] As Justin became senile almost the end of his reign, Justinian became the de facto ruler.[22] Post-obit the general Vitalian's assassination presumed to be orchestrated by Justinian or Justin, Justinian was appointed delegate in 521 and later on commander of the army of the east.[22] [27] Upon Justin's decease on 1 Baronial 527, Justinian became the sole sovereign.[25]

As a ruler, Justinian showed great free energy. He was known equally "the emperor who never sleeps" for his work habits. Nevertheless, he seems to have been amiable and easy to arroyo.[28] Around 525, he married his mistress, Theodora, in Constantinople. She was past profession an actress and some 20 years his inferior. In before times, Justinian could not have married her owing to her class, only his uncle, Emperor Justin I, had passed a law lifting restrictions on marriages with ex-actresses.[29] [30] Though the marriage acquired a scandal, Theodora would become very influential in the politics of the Empire. Other talented individuals included Tribonian, his legal adviser; Peter the Patrician, the diplomat and long-fourth dimension head of the palace bureaucracy; Justinian'due south finance ministers John the Cappadocian and Peter Barsymes, who managed to collect taxes more efficiently than any before, thereby funding Justinian's wars; and finally, his prodigiously talented generals, Belisarius and Narses.

Justinian's rule was non universally pop; early in his reign he nearly lost his throne during the Nika riots, and a conspiracy confronting the emperor's life by dissatisfied businessmen was discovered as late as 562.[31] Justinian was struck by the plague in the early 540s but recovered. Theodora died in 548[32] at a relatively young historic period, possibly of cancer; Justinian outlived her past nearly xx years. Justinian, who had always had a keen interest in theological matters and actively participated in debates on Christian doctrine,[33] became even more devoted to faith during the later years of his life. He died on 14 Nov 565,[34] childless. He was succeeded past Justin 2, who was the son of his sister Vigilantia and married to Sophia, the niece of Theodora. Justinian'due south trunk was entombed in a specially built mausoleum in the Church of the Holy Apostles until it was desecrated and robbed during the pillage of the city in 1204 by the Latin States of the Fourth Crusade.[35]

Reign [edit]

Legislative activities [edit]

Justinian achieved lasting fame through his judicial reforms, especially through the complete revision of all Roman police force,[36] something that had not previously been attempted. The total of Justinian's legislation is known today as the Corpus juris civilis. It consists of the Codex Justinianeus, the Digesta or Pandectae, the Institutiones, and the Novellae.

Early in his reign, Justinian had appointed the quaestor Tribonian to oversee this chore. The beginning draft of the Codex Justinianeus, a codification of imperial constitutions from the 2nd century onward, was issued on seven April 529. (The final version appeared in 534.) It was followed by the Digesta (or Pandectae), a compilation of older legal texts, in 533, and past the Institutiones, a textbook explaining the principles of law. The Novellae, a collection of new laws issued during Justinian's reign, supplements the Corpus. As opposed to the rest of the corpus, the Novellae appeared in Greek, the common language of the Eastern Empire.

The Corpus forms the basis of Latin jurisprudence (including ecclesiastical Catechism Law) and, for historians, provides a valuable insight into the concerns and activities of the later Roman Empire. As a collection information technology gathers together the many sources in which the leges (laws) and the other rules were expressed or published: proper laws, senatorial consults (senatusconsulta), majestic decrees, case constabulary, and jurists' opinions and interpretations (responsa prudentium). Tribonian's code ensured the survival of Roman law. It formed the basis of later Byzantine law, as expressed in the Basilika of Basil I and Leo Half-dozen the Wise. The merely western province where the Justinianic code was introduced was Italy (after the conquest past the so-called Businesslike Sanction of 554),[37] from where information technology was to laissez passer to Western Europe in the 12th century and become the basis of much Continental European law lawmaking, which eventually was spread by European empires to the Americas and beyond in the Age of Discovery. It somewhen passed to Eastern Europe where it appeared in Slavic editions, and it also passed on to Russian federation.[38] It remains influential to this day.

He passed laws to protect prostitutes from exploitation and women from being forced into prostitution. Rapists were treated severely. Further, past his policies: women charged with major crimes should be guarded past other women to prevent sexual corruption; if a adult female was widowed, her dowry should be returned; and a husband could not take on a major debt without his wife giving her consent twice.[39]

Justinian discontinued the regular date of Consuls in 541.[forty]

Nika riots [edit]

Justinian's habit of choosing efficient, but unpopular advisers nigh price him his throne early in his reign. In January 532, partisans of the chariot racing factions in Constantinople, unremarkably rivals, united against Justinian in a revolt that has get known equally the Nika riots. They forced him to dismiss Tribonian and two of his other ministers, and and so attempted to overthrow Justinian himself and replace him with the senator Hypatius, who was a nephew of the late emperor Anastasius. While the crowd was rioting in the streets, Justinian considered fleeing the capital letter by body of water, but eventually decided to stay, apparently on the prompting of his wife Theodora, who refused to get out. In the next two days, he ordered the cruel suppression of the riots by his generals Belisarius and Mundus. Procopius relates that 30,000[41] unarmed civilians were killed in the Hippodrome. On Theodora's insistence, and evidently against his own judgment,[42] Justinian had Anastasius' nephews executed.[43]

The destruction that took place during the defection provided Justinian with an opportunity to tie his name to a series of splendid new buildings, most notably the architectural innovation of the domed Hagia Sophia.

Military activities [edit]

One of the most spectacular features of Justinian'south reign was the recovery of large stretches of state around the Western Mediterranean basin that had slipped out of Purple command in the 5th century.[44] As a Christian Roman emperor, Justinian considered it his divine duty to restore the Roman Empire to its aboriginal boundaries. Although he never personally took part in military campaigns, he boasted of his successes in the prefaces to his laws and had them commemorated in art.[45] The re-conquests were in large part carried out by his general Belisarius.[n. i]

War with the Sassanid Empire, 527–532 [edit]

From his uncle, Justinian inherited ongoing hostilities with the Sassanid Empire.[46] In 530 the Persian forces suffered a double defeat at Dara and Satala, but the next yr saw the defeat of Roman forces under Belisarius nigh Callinicum.[47] Justinian then tried to brand brotherhood with the Axumites of Ethiopia and the Himyarites of Yemen against the Persians, but this failed.[48] When male monarch Kavadh I of Persia died (September 531), Justinian concluded an "Eternal Peace" (which cost him 11,000 pounds of gold)[47] with his successor Khosrau I (532). Having thus secured his eastern frontier, Justinian turned his attention to the West, where Germanic kingdoms had been established in the territories of the sometime Western Roman Empire.

Conquest of North Africa, 533–534 [edit]

The beginning of the western kingdoms Justinian attacked was that of the Vandals in North Africa. King Hilderic, who had maintained good relations with Justinian and the Due north African Catholic clergy, had been overthrown by his cousin Gelimer in 530 A.D. Imprisoned, the deposed king appealed to Justinian.

In 533, Belisarius sailed to Africa with a fleet of 92 dromons, escorting 500 transports conveying an army of nearly 15,000 men, every bit well as a number of barbarian troops. They landed at Caput Vada (modern Ras Kaboudia) in modern Tunisia. They defeated the Vandals, who were caught completely off guard, at Ad Decimum on 14 September 533 and Tricamarum in December; Belisarius took Carthage. Male monarch Gelimer fled to Mount Pappua in Numidia, but surrendered the next spring. He was taken to Constantinople, where he was paraded in a triumph. Sardinia and Corsica, the Balearic Islands, and the stronghold Septem Fratres near Gibraltar were recovered in the same campaign.[49]

In this war, the contemporary Procopius remarks that Africa was so entirely depopulated that a person might travel several days without meeting a human being, and he adds, "information technology is no exaggeration to say, that in the course of the war 5,000,000 perished by the sword, and dearth, and pestilence."

An African prefecture, centered in Carthage, was established in April 534,[fifty] only information technology would teeter on the brink of plummet during the side by side 15 years, amidst warfare with the Moors and war machine mutinies. The expanse was not completely pacified until 548,[51] merely remained peaceful thereafter and enjoyed a measure of prosperity. The recovery of Africa cost the empire almost 100,000 pounds of gold.[52]

War in Italian republic, first phase, 535–540 [edit]

As in Africa, dynastic struggles in Ostrogothic Italy provided an opportunity for intervention. The young king Athalaric had died on two October 534, and a usurper, Theodahad, had imprisoned queen Amalasuintha, Theodoric's daughter and mother of Athalaric, on the isle of Martana in Lake Bolsena, where he had her assassinated in 535. Thereupon Belisarius, with 7,500 men,[53] invaded Sicily (535) and avant-garde into Italy, sacking Naples and capturing Rome on ix Dec 536. Past that time Theodahad had been deposed by the Ostrogothic army, who had elected Vitigis as their new king. He gathered a large ground forces and besieged Rome from Feb 537 to March 538 without being able to retake the city.

Justinian sent some other full general, Narses, to Italy, simply tensions between Narses and Belisarius hampered the progress of the entrada. Milan was taken, but was presently recaptured and razed by the Ostrogoths. Justinian recalled Narses in 539. By so the military state of affairs had turned in favour of the Romans, and in 540 Belisarius reached the Ostrogothic majuscule Ravenna. In that location he was offered the title of Western Roman Emperor by the Ostrogoths at the aforementioned fourth dimension that envoys of Justinian were arriving to negotiate a peace that would get out the region north of the Po River in Gothic hands. Belisarius feigned acceptance of the offer, entered the city in May 540, and reclaimed it for the Empire.[54] And so, having been recalled by Justinian, Belisarius returned to Constantinople, taking the captured Vitigis and his married woman Matasuntha with him.

War with the Sassanid Empire, 540–562 [edit]

A golden medallion celebrating the reconquest of Africa, Advertising 534

Belisarius had been recalled in the face of renewed hostilities by the Persians. Post-obit a defection against the Empire in Armenia in the late 530s and perchance motivated by the pleas of Ostrogothic ambassadors, Rex Khosrau I broke the "Eternal Peace" and invaded Roman territory in the spring of 540.[55] He outset sacked Beroea and and then Antioch (allowing the garrison of 6,000 men to get out the city),[56] besieged Daras, and and then went on to attack the small simply strategically significant satellite kingdom of Lazica near the Black Body of water, exacting tribute from the towns he passed along his manner. He forced Justinian I to pay him 5,000 pounds of gilt, plus 500 pounds of gilt more each twelvemonth.[56]

Belisarius arrived in the Due east in 541, but after some success, was again recalled to Constantinople in 542. The reasons for his withdrawal are not known, but it may have been instigated past rumours of his disloyalty reaching the court.[57] The outbreak of the plague caused a lull in the fighting during the yr 543. The post-obit year Khosrau defeated a Byzantine army of 30,000 men,[58] but unsuccessfully besieged the major city of Edessa. Both parties made little headway, and in 545 a truce was agreed upon for the southern part of the Roman-Persian frontier. After that the Lazic State of war in the North continued for several years, until a second truce in 557, followed past a Fifty Years' Peace in 562. Nether its terms, the Persians agreed to abandon Lazica in exchange for an almanac tribute of 400 or 500 pounds of gilded (xxx,000 solidi) to be paid past the Romans.[59]

War in Italy, second phase, 541–554 [edit]

While military efforts were directed to the East, the state of affairs in Italy took a plow for the worse. Under their corresponding kings Ildibad and Eraric (both murdered in 541) and especially Totila, the Ostrogoths fabricated quick gains. After a victory at Faenza in 542, they reconquered the major cities of Southern Italy and soon held almost the entire Italian peninsula. Belisarius was sent back to Italia late in 544 just lacked sufficient troops and supplies. Making no headway, he was relieved of his control in 548. Belisarius succeeded in defeating a Gothic fleet of 200 ships.[ citation needed ] During this period the city of Rome changed easily three more times, first taken and depopulated by the Ostrogoths in Dec 546, so reconquered by the Byzantines in 547, and then over again by the Goths in January 550. Totila also plundered Sicily and attacked Greek coastlines.

Finally, Justinian dispatched a force of approximately 35,000 men (2,000 men were detached and sent to invade southern Visigothic Hispania) under the command of Narses.[sixty] The army reached Ravenna in June 552 and defeated the Ostrogoths decisively within a month at the battle of Busta Gallorum in the Apennines, where Totila was slain. Later a 2nd battle at Mons Lactarius in October that year, the resistance of the Ostrogoths was finally broken. In 554, a large-scale Frankish invasion was defeated at Casilinum, and Italian republic was secured for the Empire, though it would take Narses several years to reduce the remaining Gothic strongholds. At the cease of the war, Italy was garrisoned with an ground forces of 16,000 men.[61] The recovery of Italy cost the empire about 300,000 pounds of aureate.[52] Procopius estimated 15,000,000 Goths died.[62]

Other campaigns [edit]

Emperor Justinian reconquered many sometime territories of the Western Roman Empire, including Italia, Dalmatia, Africa, and southern Hispania.

In addition to the other conquests, the Empire established a presence in Visigothic Hispania, when the usurper Athanagild requested assistance in his rebellion against King Agila I. In 552, Justinian dispatched a strength of ii,000 men; co-ordinate to the historian Jordanes, this army was led past the octogenarian Liberius.[63] The Byzantines took Cartagena and other cities on the southeastern declension and founded the new province of Spania before being checked past their old marry Athanagild, who had by now go king. This campaign marked the apogee of Byzantine expansion.[ citation needed ]

During Justinian'southward reign, the Balkans suffered from several incursions by the Turkic and Slavic peoples who lived n of the Danube. Here, Justinian resorted mainly to a combination of diplomacy and a organisation of defensive works. In 559 a especially unsafe invasion of Sklavinoi and Kutrigurs under their khan Zabergan threatened Constantinople, but they were repulsed by the anile general Belisarius.[64]

Results [edit]

Justinian's ambition to restore the Roman Empire to its onetime glory was only partly realized. In the West, the bright early military machine successes of the 530s were followed past years of stagnation. The dragging war with the Goths was a disaster for Italian republic, fifty-fifty though its long-lasting effects may have been less astringent than is sometimes idea.[65] The heavy taxes that the administration imposed upon its population were securely resented.

The last victory in Italy and the conquest of Africa and the coast of southern Hispania significantly enlarged the expanse of Byzantine influence and eliminated all naval threats to the empire, which in 555 reached its territorial zenith. Despite losing much of Italy soon subsequently Justinian's death, the empire retained several important cities, including Rome, Naples, and Ravenna, leaving the Lombards every bit a regional threat. The newly founded province of Spania kept the Visigoths as a threat to Hispania alone and not to the western Mediterranean and Africa.

Events of the later years of his reign showed that Constantinople itself was non safe from barbarian incursions from the north, and even the relatively chivalrous historian Menander Protector felt the need to attribute the Emperor'southward failure to protect the capital to the weakness of his body in his old age.[66] In his efforts to renew the Roman Empire, Justinian dangerously stretched its resources while failing to accept into account the inverse realities of 6th-century Europe.[67]

Religious activities [edit]

| Saint Justinian the Swell | |

|---|---|

Analogy of an angel showing Justinian a model of Hagia Sophia in a vision, by Herbert Cole (1912) | |

| Emperor | |

| Venerated in |

|

| Major shrine | Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople modern twenty-four hours Istanbul, Turkey |

| Feast | 14 Nov |

| Attributes | Royal Vestment |

Justinian I, depicted on an AE Follis money

Justinian saw the orthodoxy of his empire threatened by diverging religious currents, specially Monophysitism, which had many adherents in the eastern provinces of Syrian arab republic and Egypt. Monophysite doctrine, which maintains that Jesus Christ had i divine nature rather than a synthesis of divine and human nature, had been condemned as a heresy by the Council of Chalcedon in 451, and the tolerant policies towards Monophysitism of Zeno and Anastasius I had been a source of tension in the relationship with the bishops of Rome. Justin reversed this tendency and confirmed the Chalcedonian doctrine, openly condemning the Monophysites. Justinian, who continued this policy, tried to impose religious unity on his subjects by forcing them to accept doctrinal compromises that might entreatment to all parties, a policy that proved unsuccessful every bit he satisfied none of them.[68]

Near the cease of his life, Justinian became ever more inclined towards the Monophysite doctrine, especially in the form of Aphthartodocetism, but he died earlier being able to issue any legislation. The empress Theodora sympathized with the Monophysites and is said to accept been a constant source of pro-Monophysite intrigues at the courtroom in Constantinople in the earlier years. In the class of his reign, Justinian, who had a genuine interest in matters of theology, authored a pocket-size number of theological treatises.[69]

Religious policy [edit]

Hagia Sophia mosaic depicting the Virgin Mary property the Child Christ on her lap. On her right side stands Justinian, offering a model of the Hagia Sophia. On her left, Constantine I presents a model of Constantinople.

As in his secular administration, despotism appeared also in the Emperor's ecclesiastical policy. He regulated everything, both in religion and in law.

At the very beginning of his reign, he deemed it proper to promulgate by police force the Church's belief in the Trinity and the Incarnation, and to threaten all heretics with the appropriate penalties,[70] whereas he after alleged that he intended to deprive all disturbers of orthodoxy of the opportunity for such offense by due process of police force.[71] He fabricated the Nicaeno-Constantinopolitan creed the sole symbol of the Church building[72] and accorded legal force to the canons of the four ecumenical councils.[73] The bishops in omnipresence at the Council of Constantinople (536) recognized that zip could be washed in the Church contrary to the emperor's will and control,[74] while, on his side, the emperor, in the case of the Patriarch Anthimus, reinforced the ban of the Church with temporal proscription.[75] Justinian protected the purity of the church past suppressing heretics. He neglected no opportunity to secure the rights of the Church and clergy, and to protect and extend monasticism. He granted the monks the right to inherit property from private citizens and the right to receive solemnia, or almanac gifts, from the Royal treasury or from the taxes of certain provinces and he prohibited lay confiscation of monastic estates.

Although the despotic character of his measures is contrary to mod sensibilities, he was indeed a "nursing male parent" of the Church. Both the Codex and the Novellae comprise many enactments regarding donations, foundations, and the administration of ecclesiastical belongings; election and rights of bishops, priests and abbots; monastic life, residential obligations of the clergy, conduct of divine service, episcopal jurisdiction, etc. Justinian as well rebuilt the Church building of Hagia Sophia (which cost twenty,000 pounds of gilded),[76] the original site having been destroyed during the Nika riots. The new Hagia Sophia, with its numerous chapels and shrines, gilded octagonal dome, and mosaics, became the heart and most visible monument of Eastern Orthodoxy in Constantinople.[ citation needed ]

Religious relations with Rome [edit]

Consular diptych displaying Justinian'southward total name (Constantinople 521)

From the middle of the 5th century onward, increasingly backbreaking tasks confronted the emperors of the East in ecclesiastical matters. Justinian entered the arena of ecclesiastical statecraft shortly after his uncle's accession in 518, and put an end to the Acacian schism. Previous Emperors had tried to convalesce theological conflicts by declarations that deemphasized the Council of Chalcedon, which had condemned Monophysitism, which had strongholds in Arab republic of egypt and Syria, and by tolerating the appointment of Monophysites to church building offices. The Popes reacted past severing ties with the Patriarch of Constantinople who supported these policies. Emperors Justin I (and afterwards Justinian himself) rescinded these policies and reestablished the matrimony betwixt Constantinople and Rome.[77] Later this, Justinian as well felt entitled to settle disputes in papal elections, as he did when he favoured Vigilius and had his rival Silverius deported.

This new-found unity between East and West did not, however, solve the ongoing disputes in the east. Justinian's policies switched between attempts to force Monophysites and Miaphysites (who were mistaken to be adherers of Monophysitism) to have the Chalcedonian creed past persecuting their bishops and monks – thereby embittering their sympathizers in Arab republic of egypt and other provinces – and attempts at a compromise that would win over the Monophysites without surrendering the Chalcedonian faith. Such an approach was supported by the Empress Theodora, who favoured the Miaphysites unreservedly. In the condemnation of the Three Capacity, three theologians that had opposed Monophysitism before and later the Council of Chalcedon, Justinian tried to win over the opposition. At the Fifth Ecumenical Council, most of the Eastern church yielded to the Emperor's demands, and Pope Vigilius, who was forcibly brought to Constantinople and besieged at a chapel, finally also gave his assent. Even so, the condemnation was received unfavourably in the w, where it led to new (albeit temporal) schism, and failed to reach its goal in the east, equally the Monophysites remained unsatisfied – all the more bitter for him because during his last years he took an even greater interest in theological matters.

[edit]

Justinian was ane of the outset Roman Emperors to exist depicted holding the cantankerous-surmounted orb on the obverse of a coin.

Justinian's religious policy reflected the Purple confidence that the unity of the Empire presupposed unity of religion, and it appeared to him obvious that this faith could only be the orthodoxy (Chalcedonian). Those of a different conventionalities were subjected to persecution, which imperial legislation had effected from the time of Constantius 2 and which would now vigorously continue. The Codex contained ii statutes[78] that decreed the total destruction of paganism, even in private life; these provisions were zealously enforced. Contemporary sources (John Malalas, Theophanes, and John of Ephesus) tell of severe persecutions, fifty-fifty of men in high position.[ dubious ]

The original Academy of Plato had been destroyed by the Roman dictator Sulla in 86 BC. Several centuries later, in 410 Advertizement, a Neoplatonic Academy was established that had no institutional continuity with Plato's Academy, and which served as a center for Neoplatonism and mysticism. It persisted until 529 Advertizement when it was finally closed past Justinian I. Other schools in Constantinople, Antioch, and Alexandria, which were the centers of Justinian'due south empire, continued.[79]

In Asia Pocket-size alone, John of Ephesus was reported to have converted lxx,000 pagans, which was probably an exaggerated number.[lxxx] Other peoples too accustomed Christianity: the Heruli,[81] the Huns dwelling virtually the Don,[82] the Abasgi,[83] and the Tzanni in Caucasia.[84]

The worship of Amun at the haven of Awjila in the Libyan desert was abolished,[85] and then were the remnants of the worship of Isis on the island of Philae, at the first cataract of the Nile.[86] The Presbyter Julian[87] and the Bishop Longinus[88] conducted a mission amid the Nabataeans, and Justinian attempted to strengthen Christianity in Republic of yemen by dispatching a bishop from Arab republic of egypt.[89]

The civil rights of Jews were restricted[90] and their religious privileges threatened.[91] Justinian also interfered in the internal affairs of the synagogue[92] and encouraged the Jews to utilize the Greek Septuagint in their synagogues in Constantinople.[93]

The Emperor faced significant opposition from the Samaritans, who resisted conversion to Christianity and were repeatedly in insurrection. He persecuted them with rigorous edicts, but could non prevent reprisals towards Christians from taking place in Samaria toward the close of his reign. The consistency of Justinian'southward policy meant that the Manicheans likewise suffered persecution, experiencing both exile and threat of death sentence.[94] At Constantinople, on one occasion, non a few Manicheans, after strict inquisition, were executed in the emperor'due south very presence: some by burning, others by drowning.[95]

Compages, learning, art and literature [edit]

The church of Hagia Sophia was built at the time of Justinian.

Justinian was a prolific builder; the historian Procopius bears witness to his activities in this area.[96] Under Justinian'southward reign, the San Vitale in Ravenna, which features 2 famous mosaics representing Justinian and Theodora, was completed under the sponsorship of Julius Argentarius.[22] About notably, he had the Hagia Sophia, originally a basilica-style church that had been burnt down during the Nika riots, splendidly rebuilt co-ordinate to a completely different ground program, nether the architectural supervision of Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. Co-ordinate to Pseudo-Codinus, Justinian stated at the completion of this edifice, "Solomon, I have outdone thee" (in reference to the start Jewish temple). This new cathedral, with its magnificent dome filled with mosaics, remained the middle of eastern Christianity for centuries.[ citation needed ]

Another prominent church building in the capital, the Church of the Holy Apostles, which had been in a very poor land near the stop of the 5th century, was likewise rebuilt.[97] The Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, later renamed Little Hagia Sophia, was besides built between 532 and 536 past the imperial couple.[98] Works of embellishment were not confined to churches lonely: excavations at the site of the Cracking Palace of Constantinople accept yielded several loftier-quality mosaics dating from Justinian's reign, and a column topped by a statuary statue of Justinian on horseback and dressed in a military costume was erected in the Augustaeum in Constantinople in 543.[99] Rivalry with other, more than established patrons from the Constantinopolitan and exiled Roman aristocracy might have enforced Justinian's building activities in the capital as a means of strengthening his dynasty'due south prestige.[100]

Justinian besides strengthened the borders of the Empire from Africa to the East through the construction of fortifications and ensured Constantinople of its water supply through construction of hole-and-corner cisterns (see Basilica Cistern). To prevent floods from dissentious the strategically important border town Dara, an avant-garde arch dam was congenital. During his reign the big Sangarius Bridge was built in Bithynia, securing a major military supply road to the east. Furthermore, Justinian restored cities damaged by earthquake or state of war and congenital a new city near his place of birth called Justiniana Prima, which was intended to replace Thessalonica as the political and religious heart of Illyricum.

In Justinian's reign, and partly nether his patronage, Byzantine culture produced noteworthy historians, including Procopius and Agathias, and poets such equally Paul the Silentiary and Romanus the Melodist flourished. On the other manus, centres of learning such every bit the Neoplatonic Academy in Athens and the famous Law Schoolhouse of Berytus[101] lost their importance during his reign.[ citation needed ]

Economy and administration [edit]

Gold money of Justinian I (527–565) excavated in India probably in the due south, an example of Indo-Roman trade during the flow

As was the case under Justinian'due south predecessors, the Empire's economic health rested primarily on agriculture. In addition, long-distance trade flourished, reaching every bit far north as Cornwall where can was exchanged for Roman wheat.[102] Within the Empire, convoys sailing from Alexandria provided Constantinople with wheat and grains. Justinian fabricated the traffic more efficient past building a large granary on the isle of Tenedos for storage and farther transport to Constantinople.[103] Justinian as well tried to discover new routes for the eastern merchandise, which was suffering badly from the wars with the Persians.

Ane important luxury product was silk, which was imported and and so processed in the Empire. In society to protect the manufacture of silk products, Justinian granted a monopoly to the imperial factories in 541.[104] In society to bypass the Persian landroute, Justinian established friendly relations with the Abyssinians, whom he wanted to deed every bit trade mediators by transporting Indian silk to the Empire; the Abyssinians, however, were unable to compete with the Persian merchants in India.[105] Then, in the early 550s, 2 monks succeeded in smuggling eggs of silk worms from Central Asia back to Constantinople,[106] and silk became an indigenous product.

Golden and silver were mined in the Balkans, Anatolia, Armenia, Republic of cyprus, Egypt and Nubia.[107]

At the start of Justinian I's reign he had inherited a surplus 28,800,000 solidi (400,000 pounds of gold) in the royal treasury from Anastasius I and Justin I.[52] Nether Justinian's rule, measures were taken to counter corruption in the provinces and to make tax collection more than efficient. Greater authoritative power was given to both the leaders of the prefectures and of the provinces, while power was taken abroad from the vicariates of the dioceses, of which a number were abolished. The overall trend was towards a simplification of administrative infrastructure.[108] According to Brown (1971), the increased professionalization of tax collection did much to destroy the traditional structures of provincial life, as it weakened the autonomy of the town councils in the Greek towns.[109] Information technology has been estimated that before Justinian I's reconquests the state had an almanac revenue of 5,000,000 solidi in Advertizement 530, but after his reconquests, the annual acquirement was increased to 6,000,000 solidi in Advertising 550.[52]

Throughout Justinian'southward reign, the cities and villages of the E prospered, although Antioch was struck by two earthquakes (526, 528) and sacked and evacuated past the Persians (540). Justinian had the city rebuilt, but on a slightly smaller scale.[110]

Despite all these measures, the Empire suffered several major setbacks in the course of the 6th century. The first one was the plague, which lasted from 541 to 543 and, past decimating the Empire's population, probably created a scarcity of labor and a ascension of wages.[111] The lack of manpower likewise led to a significant increase in the number of "barbarians" in the Byzantine armies afterward the early on 540s.[112] The protracted war in Italy and the wars with the Persians themselves laid a heavy brunt on the Empire's resource, and Justinian was criticized for curtailing the regime-run post service, which he limited to only ane eastern road of armed services importance.[113]

Natural disasters [edit]

During the 530s, information technology seemed to many that God had abandoned the Christian Roman Empire. There were noxious fumes in the air and the Sun, while still providing daylight, refused to requite much heat. The extreme weather events of 535–536 led to a famine such equally had not been recorded before, affecting both Europe and the Middle East.[114] These events may have been caused by an atmospheric grit veil resulting from a large volcanic eruption.[115] [116]

The historian Procopius recorded in 536 in his work on the Vandalic State of war "during this year a most dread portent took identify. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness … and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were non articulate".[117] [118]

The causes of these disasters are not precisely known, but volcanoes at the Rabaul caldera, Lake Ilopango, Krakatoa, or, according to a recent finding, in Iceland are suspected,[114] as is an air burst event from a comet fragment. [ citation needed ]

Vii years later in 542, a devastating outbreak of Bubonic Plague, known as the Plague of Justinian and second simply to Black Death of the 14th century, killed tens of millions. Justinian and members of his court, physically unaffected past the previous 535–536 famine, were afflicted, with Justinian himself contracting and surviving the pestilence. The impact of this outbreak of plague has recently been disputed, since evidence for tens of millions dying is uncertain.[119] [120]

In July 551, the eastern Mediterranean was rocked by the 551 Beirut earthquake, which triggered a seismic sea wave. The combined fatalities of both events likely exceeded 30,000, with tremors felt from Antioch to Alexandria.[121]

Cultural depictions [edit]

In the Paradiso section of the Divine One-act , Canto (chapter) Vi, by Dante Alighieri, Justinian I is prominently featured equally a spirit residing on the sphere of Mercury. The latter holds in Heaven the souls of those whose acts were righteous, yet meant to achieve fame and honor. Justinian'southward legacy is elaborated on, and he is portrayed every bit a defender of the Christian faith and the restorer of Rome to the Empire. Justinian confesses that he was partially motivated by fame rather than duty to God, which tainted the justice of his dominion in spite of his proud accomplishments. In his introduction, "Cesare fui e son Iustinïano" ("Caesar I was, and am Justinian"[123]), his mortal title is assorted with his immortal soul, to emphasize that "glory in life is imperceptible, while contributing to God's glory is eternal", according to Dorothy L. Sayers.[124] Dante also uses Justinian to criticize the factious politics of his 14th Century Italia, divided between Ghibellines and Guelphs, in contrast to the unified Italy of the Roman Empire.

Justinian is a major grapheme in the 1938 novel Count Belisarius, by Robert Graves. He is depicted as a jealous and conniving Emperor obsessed with creating and maintaining his own historical legacy.

Justinian appears as a grapheme in the 1939 time travel novel Lest Darkness Fall, by L. Sprague de Campsite.

The Glittering Horn: Secret Memoirs of the Court of Justinian was a novel written by Pierson Dixon in 1958 nearly the courtroom of Justinian.

Justinian occasionally appears in the comic strip Prince Valiant, usually as a nemesis of the title character.

Justinian is played by Innokenty Smoktunovsky in the 1985 Soviet film Master Russia

Historical sources [edit]

Procopius provides the primary source for the history of Justinian'southward reign, only his opinion is tainted by a feeling of betrayal when Justinian became more businesslike and less idealistic (Justinian and the After Roman Empire by John W. Barker). He became very bitter towards Justinian and his empress, Theodora.[due north. two] The Syriac chronicle of John of Ephesus, which survives partially, was used as a source for after chronicles, contributing many additional details of value. Other sources include the writings of John Malalas, Agathias, John the Lydian, Menander Protector, the Paschal Chronicle, Evagrius Scholasticus, Pseudo-Zacharias Rhetor, Jordanes, the chronicles of Marcellinus Comes and Victor of Tunnuna. Justinian is widely regarded every bit a saint by Orthodox Christians, and is also commemorated by some Lutheran churches on 14 November.[n. 3]

See likewise [edit]

- Church building of the Nascency in Bethlehem, rebuilt by Justinian

- Flavia gens

- International Roman Police force Moot Court

Notes [edit]

- ^ Justinian himself took the field only once, during a campaign confronting the Huns in 559, when he was already an old man. This enterprise was largely symbolic and although no battle was fought, the emperor held a triumphal entry in the majuscule afterwards. (See Browning, R. Justinian and Theodora. London 1971, 193.)

- ^ While he glorified Justinian's achievements in his panegyric and his Wars, Procopius likewise wrote a hostile account, Anekdota (the then-called Secret History), in which Justinian is depicted as a brutal, venal, and incompetent ruler.

- ^ In various Eastern Orthodox Churches, including the Orthodox Church in America, Justinian and his empress Theodora are commemorated on the anniversary of his death, 14 Nov. Some denominations translate the Julian calendar date to 27 November on the Gregorian calendar. The Agenda of Saints of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod and the Lutheran Church building–Canada as well remember Justinian on fourteen November.

References [edit]

- ^ J. B. Bury (2008) [1889] History of the Subsequently Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene II. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 1605204056, p. 7.

- ^ J. F. Haldon, Byzantium in the seventh century (Cambridge, 2003), 17–19.

- ^ On the western Roman Empire, see at present H. Börm, Westrom (Stuttgart 2013).

- ^ "History 303: Finances under Justinian". Tulane.edu. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Evans, J. A. Due south., The Age of Justinian: the circumstances of regal power. pp. 93–94

- ^ John Henry Merryman and Rogelio Pérez-Perdomo, The Civil Law Tradition: An Introduction to the Legal Systems of Europe and Latin America, third ed. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), pp. ix–11.

- ^ "St. Justinian the Emperor". Orthodox Church in America . Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ For instance by George Philip Baker (Justinian, New York 1938), or in the Outline of Great Books series (Justinian the Slap-up).

- ^ near Skopje, North Macedonia

- ^ Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2008, ISBN 1593394926, p. 1007.

- ^ The Inheritance of Rome, Chris Wickham, Penguin Books Ltd. 2009, ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0 (p. xc). Justinian referred to Latin as his native tongue in several of his laws. Meet Moorhead (1994), p. 18.

- ^ Michael Maas (2005). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-1139826877.

- ^ Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A history of the Byzantine state and gild. Stanford Academy Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8047-2630-6. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Barker, John Due west. (1966). Justinian and the afterwards Roman Empire. University of Wisconsin Printing. p. 75. ISBN978-0-299-03944-eight . Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Robert Browning (2003). Justinian and Theodora. Gorgias Printing. ISBN978-1593330538.

- ^ Shifting Genres in Tardily Antiquity, Hugh Elton, Geoffrey Greatrex, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2015, ISBN 1472443500, p. 259.

- ^ Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire, András Mócsy, Routledge, 2014, ISBN 1317754255, p. 350.

- ^ The sole source for Justinian's full proper name, Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus (sometimes called Flavius Anicius Iustinianus), are consular diptychs of the yr 521 begetting his name.

- ^ Sima One thousand. Cirkovic (2004). The Serbs. Wiley. ISBN978-0631204718.

- ^ Justiniana Prima Site of an early Byzantine city located thirty km southward-west of Leskovci in Kosovo. Grove'south Dictionaries. 2006.

- ^ Byzantine Constantinople: Monuments, Topography and Everyday Life. Brill. 2001. ISBN978-9004116252.

- ^ a b c d e f m Robert Browning. "Justinian I" in Dictionary of the Centre Ages, volume 7 (1986).

- ^ Martindale, PLRE Two 646

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History p. 65

- ^ a b Chronicon Paschale 527; Theophanes Confessor AM 6019.

- ^ Moorhead (1994), pp. 21–22, with a reference to Procopius, Underground History 8.3.

- ^ This post seems to have been titular; there is no bear witness that Justinian had whatsoever military feel. See A.D. Lee, "The Empire at War", in Michael Maas (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian (Cambridge 2005), pp. 113–133 (pp. 113–114).

- ^ See Procopius, Hugger-mugger history, ch. thirteen.

- ^ M. Meier, Justinian, p. 57.

- ^ P. N. Ure, Justinian and his age, p. 200.

- ^ "DIR Justinian". Roman Emperors. 25 July 1998. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Robert Browning, Justinian and Theodora (1987), 129; James Allan Evans, The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian (2002), 104

- ^ Theological treatises authored by Justinian tin be found in Migne's Patrologia Graeca, Vol. 86.

- ^ Chronicon Paschale 566; John of Ephesus Iii 5.13.; Theophanes Confessor AM 6058; John Malalas 18.1.

- ^ Crowley, Roger (2011). City of Fortune, How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire. London: Faber & Faber Ltd. p. 109. ISBN978-0-571-24595-6.

- ^ "S. P. Scott: The Civil Law". Constitution.org. 19 June 2002. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Kunkel, W. (translated by J. 1000. Kelly) An introduction to Roman legal and constitutional history. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1966; 168

- ^ Darrell P. Hammer (1957). "Russia and the Roman Law". American Slavic and East European Review. JSTOR. 16 (one): 1–xiii. doi:10.2307/3001333. JSTOR 3001333.

- ^ Garland (1999), pp. 16–17

- ^ Vasiliev (1952), p. I 192.

- ^ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, 200

- ^ Diehl, Charles. Theodora, Empress of Byzantium ((c) 1972 past Frederick Ungar Publishing, Inc., transl. past S.R. Rosenbaum from the original French Theodora, Imperatice de Byzance), 89.

- ^ Vasiliev (1958), p. 157.

- ^ For an account of Justinian'due south wars, see Moorhead (1994), pp. 22–24, 63–98, and 101–109.

- ^ See A. D. Lee, "The Empire at War", in Michael Maas (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian (Cambridge 2005), pp. 113–33 (pp. 113–114). For Justinian's own views, see the texts of Codex Iustinianus one.27.1 and Novellae 8.x.2 and 30.11.ii.

- ^ Encounter Geoffrey Greatrex, "Byzantium and the East in the Sixth Century" in Michael Maas (ed.). Age of Justinian (2005), pp. 477–509.

- ^ a b J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, p. 195.

- ^ Smith, Sidney (1954). "Events in Arabia in the sixth Century A.D.". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. sixteen (iii): 425–468. doi:x.1017/S0041977X00086791. JSTOR 608617.

- ^ Moorhead (1994), p. 68.

- ^ Moorhead (1994), p. 70.

- ^ Procopius. "II.XXVIII". De Bello Vandalico.

- ^ a b c d "Early Medieval and Byzantine Civilization: Constantine to Crusades". Tulane. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008.

- ^ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early on Centuries, 215

- ^ Moorhead (1994), pp. 84–86.

- ^ Encounter for this section Moorhead (1994), pp. 89 ff., Greatrex (2005), p. 488 ff., and peculiarly H. Börm, "Der Perserkönig im Imperium Romanum", in Chiron 36, 2006, pp. 299 ff.

- ^ a b J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early on Centuries, 229

- ^ Procopius mentions this event both in the Wars and in the Secret History, but gives two entirely different explanations for it. The evidence is briefly discussed in Moorhead (1994), pp. 97–98.

- ^ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, 235

- ^ Moorhead ((1994), p. 164) gives the lower, Greatrex ((2005), p. 489) the higher figure.

- ^ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, 251

- ^ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, 233

- ^ Mavor, William Fordyce (1 March 1802). "Universal history, ancient and modern" – via Google Books.

- ^ Getica, 303

- ^ Evans, James Allan (2011). The Power Game in Byzantium : Antonina and the Empress Theodora. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 205–206. ISBN978-1-4411-2040-3. OCLC 843198707.

- ^ See Lee (2005), pp. 125 ff.

- ^ W. Pohl, "Justinian and the Barbaric Kingdoms", in Maas (2005), pp. 448–476; 472

- ^ See Haldon (2003), pp. 17–xix.

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, pp. 207–250.

- ^ Treatises written by Justinian can be found in Migne'due south Patrologia Graeca, Vol. 86.

- ^ Cod., I., i. 5.

- ^ MPG, lxxxvi. one, p. 993.

- ^ Cod., I., i. 7.

- ^ Novellae, cxxxi.

- ^ Mansi, Concilia, eight. 970B.

- ^ Novellae, xlii.

- ^ P. Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, 283

- ^ cf. Novellae, cxxxi.

- ^ Cod., I., 11. 9 and 10.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. "The Beginnings of Western Science", p. 70

- ^ François Nau, in Revue de l'orient chretien, ii., 1897, 482.

- ^ Procopius, Bellum Gothicum, ii. fourteen; Evagrius, Hist. eccl., iv. 20

- ^ Procopius, iv. 4; Evagrius, iv. 23.

- ^ Procopius, iv. 3; Evagrius, iv. 22.

- ^ Procopius, Bellum Persicum, i. xv.

- ^ Procopius, De Aedificiis, vi. 2.

- ^ Procopius, Bellum Persicum, i. xix.

- ^ DCB, 3. 482

- ^ John of Ephesus, Hist. eccl., iv. v sqq.

- ^ Procopius, Bellum Persicum, i. 20; Malalas, ed. Niebuhr, Bonn, 1831, pp. 433 sqq.

- ^ Cod., I., v. 12

- ^ Procopius, Historia Arcana, 28;

- ^ Nov., cxlvi., 8 February 553

- ^ Michael Maas (2005), The Cambridge companion to the Age of Justinian, Cambridge Academy Printing, pp. 16–, ISBN978-0-521-81746-ii , retrieved 18 August 2010

- ^ Cod., I., five. 12.

- ^ F. Nau, in Revue de l'orient, ii., 1897, p. 481.

- ^ See Procopius, Buildings.

- ^ Vasiliev (1952), p. 189

- ^ Bardill, Jonathan (2017). "The Date, Dedication, and Design of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople". Journal of Late Antiquity. 10 (1): 62–130. doi:10.1353/jla.2017.0003. ISSN 1942-1273.

- ^ Brian Croke, "Justinian'due south Constantinople", in Michael Maas (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian (Cambridge 2005), pp. 60–86 (p. 66)

- ^ See Croke (2005), pp. 364 ff., and Moorhead (1994).

- ^ Following a terrible earthquake in 551, the school at Berytus was transferred to Sidon and had no further significance afterward that date. (Vasiliev (1952), p. 147)

- ^ John F. Haldon, "Economy and Administration", in Michael Maas (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian (Cambridge 2005), pp. 28–59 (p. 35)

- ^ John Moorhead, Justinian (London/New York 1994), p. 57

- ^ Peter Brown, The World of Late Antiquity (London 1971), pp. 157–158

- ^ Vasiliev (1952), p. 167

- ^ See Moorhead (1994), p. 167; Procopius, Wars, eight.17.1–8

- ^ "Justinian's Gilt Mines – Mining Technology | TechnoMine". Technology.infomine.com. 3 December 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Haldon (2005), p. fifty

- ^ Brownish (1971), p. 157

- ^ Kenneth Yard. Holum, "The Classical Urban center in the Sixth Century", in Michael Maas (ed.), Age of Justinian (2005), pp. 99–100

- ^ Moorhead (1994), pp. 100–101

- ^ John L. Teall, "The Barbarians in Justinian'south Armies", in Speculum, vol. forty, No. ii, 1965, 294–322. The total strength of the Byzantine army under Justinian is estimated at 150,000 men (J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early on Centuries, 259).

- ^ Brown (1971), p. 158; Moorhead (1994), p. 101

- ^ a b Gibbons, Ann (fifteen Nov 2018). "Why 536 was 'the worst year to be alive'". Science. doi:x.1126/science.aaw0632. S2CID 189287084.

- ^ Larsen, Fifty. B.; Vinther, B. Thou.; Briffa, K. R.; Melvin, T. M.; Clausen, H. B.; Jones, P. D.; Siggaard-Andersen, K.-L.; Hammer, C. U.; et al. (2008). "New water ice core evidence for a volcanic cause of the A.D. 536 dust veil". Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (4): L04708. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3504708L. doi:x.1029/2007GL032450.

- ^ Than, Ker (3 January 2009). "Slam dunks from space led to hazy shade of wintertime". New Scientist. 201 (2689): 9. Bibcode:2009NewSc.201....9P. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(09)60069-5.

- ^ Procopius; Dewing, Henry Bronson, trans. (1916). Procopius. Vol. 2: History of the [Vandalic] Wars, Books Three and Iv. London, England: William Heinemann. p. 329. ISBN978-0-674-99054-8.

- ^ Ochoa, George; Jennifer Hoffman; Tina Tin (2005). Climate: the force that shapes our world and the future of life on world. Emmaus, PA: Rodale. ISBN978-one-59486-288-5.

- ^ Mordechai, Lee; Eisenberg, Merle; Newfield, Timothy P.; Izdebski, Adam; Kay, Janet Eastward.; Poinar, Hendrik (27 November 2019). "The Justinianic Plague: An inconsequential pandemic?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (51): 25546–25554. doi:x.1073/pnas.1903797116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC6926030. PMID 31792176.

- ^ Mordechai, Lee; Eisenberg, Merle (1 Baronial 2019). "Rejecting Catastrophe: The Example of the Justinianic Plague". Past & Present. 244 (1): 3–50. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtz009. ISSN 0031-2746.

- ^ Sbeinati, K. R.; Darawcheh, R.; Mouty, M. (25 Dec 2005). "The historical earthquakes of Syria: an analysis of large and moderate earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D." Annals of Geophysics. 48 (3). doi:10.4401/ag-3206. ISSN 2037-416X.

- ^ Yuri Marano (2012). "Discussion: Porphyry caput of emperor ('Justinian'). From Constantinople (at present in Venice). Early sixth century". Last Statues of Antiquity (LSA Database), University of Oxford.

- ^ Paradiso, Canto Half-dozen poesy 10

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradiso, notes on Canto 6.

- This article incorporates text from the Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge.

Chief sources [edit]

- Procopius, Historia Arcana.

- The Anecdota or Clandestine History. Edited past H. B. Dewing. 7 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Harvard Academy Press and London, Hutchinson, 1914–forty. Greek text and English translation.

- Procopii Caesariensis opera omnia. Edited by J. Haury; revised past G. Wirth. 3 vols. Leipzig: Teubner, 1962–64. Greek text.

- The Secret History, translated past G.A. Williamson. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1966. A readable and accessible English translation of the Anecdota.

- John Malalas, Relate, translated by Elizabeth Jeffreys, Michael Jeffreys & Roger Scott, 1986. Byzantina Australiensia 4 (Melbourne: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies) ISBN 0-9593626-2-2

- Evagrius Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History, translated by Edward Walford (1846), reprinted 2008. Evolution Publishing, ISBN 978-1-889758-88-6.

Bibliography [edit]

- Barker, John W. (1966). Justinian and the Later Roman Empire. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN978-0299039448.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Bury, J. B. (1958). History of the afterwards Roman Empire. Vol. ii. New York (reprint).

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church building in history. Vol. two. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN978-0-88-141056-3.

- Cameron, Averil; et al., eds. (2000). "Justinian Era". The Cambridge Aboriginal History (2d ed.). Cambridge. 14.

- Cumberland Jacobsen, Torsten (2009). The Gothic War. Westholme.

- Dixon, Pierson (1958). The Glittering Horn: Secret Memoirs of the Court of Justinian.

- Evans, James Allan (2005). The Emperor Justinian and the Byzantine Empire. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN978-0-313-32582-3.

- Garland, Lynda (1999). Byzantine empresses: women and power in Byzantium, Advertising 527–1204. London: Routledge.

- Maas, Michael, ed. (2005). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge.

- Martindale, J.R., ed. (1980). "Fl. Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus". Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Vol. II. pp. 645–648.

- Meier, Mischa (2003). Das andere Zeitalter Justinians. Kontingenz Erfahrung und Kontingenzbewältigung im 6. Jahrhundert northward. Chr (in German). Gottingen.

- Meier, Mischa (2004). Justinian. Herrschaft, Reich, und Faith (in German). Munich.

- Moorhead, John (1994). Justinian. London.

- Rosen, William (2007). Justinian'south Flea: Plague, Empire, and the Nascence of Europe . Viking Adult. ISBN978-0-670-03855-8.

- Rubin, Berthold (1960). Das Zeitalter Iustinians. Berlin. – German standard work; partially obsolete, merely still useful.

- Sarris, Peter (2006). Economy and society in the age of Justinian. Cambridge.

- Ure, PN (1951). Justinian and his Historic period. Penguin, Harmondsworth.

- Vasiliev, A. A. (1952). History of the Byzantine Empire (Second ed.). Madison.

- Sidney Dean; Duncan B. Campbell; Ian Hughes; Ross Cowan; Raffaele D'Amato; Christopher Lillington-Martin, eds. (June–July 2010). "Justinian'due south fireman: Belisarius and the Byzantine empire". Ancient Warfare. IV (iii).

- Turlej, Stanisław (2016). Justiniana Prima: An Underestimated Aspect of Justinian's Church Policy. Krakow: Jagiellonian University Printing. ISBN978-8323395560.

External links [edit]

- Kettenhofen, Erich (2009). "Justinian I". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XV, Fasc. 3. pp. 257–262.

- St Justinian the Emperor Orthodox Icon and Synaxarion (xiv November)

- The Anekdota ("Hugger-mugger history") of Procopius in English translation.

- Lewis E 244 Infortiatum at OPenn

- The Buildings of Procopius in English translation.

- The Roman Police force Library by Professor Yves Lassard and Alexandr Koptev

- Lecture series roofing 12 Byzantine Rulers, including Justinian – by Lars Brownworth

- De Imperatoribus Romanis. An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors

- Reconstruction of cavalcade of Justinian in Constantinople

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes

- Preface to the Digest of Emperor Justinian

- Annotated Justinian Lawmaking (University of Wyoming website)

- Mosaic of Justinian in Hagia Sophia

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Justinian_I

Postar um comentário for "This Time Was Already Accounted for on 527 I Placed It Here Again for Illustration Purposes"